Autumn in New York along part of the northern boundary of the Manhattan road price zone. Photo nycgo.com

Missing trips, lost revenue

Last time we stopped by Seattle and Louisville and saw trivial asset fees slash loads in half, leaving billion-dollar debts to be serviced by a meagre revenue stream.

Hindsight suggests that, rather than building before tolling, it would have been wiser to toll first. Pre-emptive tolling on the existing roads could have cut the load before the loan commitment was made and revealed that these megaprojects could have been postponed, revised, or abandoned.

Unfortunately, prevention through hindsight is a remedy not yet available, not even on prescription. So, how could these two cities get out of their predicament?

When the tolls cut much of loads in Seattle and Louisville, we speculated that some of the trips would have evaporated as drivers chose other destinations, worked out other ways to get things done or switched modes. This, as we will see, is what occurred in Stockholm.

But some of the trips that went missing at the toll point would have persisted on their drive through the corridor but diverted around the tollbooths via the surface roads in Seattle and via the un-tolled bridge downstream in Louisville.

The road price solution to the problem (and there are several non-price solutions) is to bring the toll-avoiding group to the cash register by switching from a site-based toll point to a zone-based corridor charge. This would ensure that every trip through the corridor paid the toll.

A corridor charge

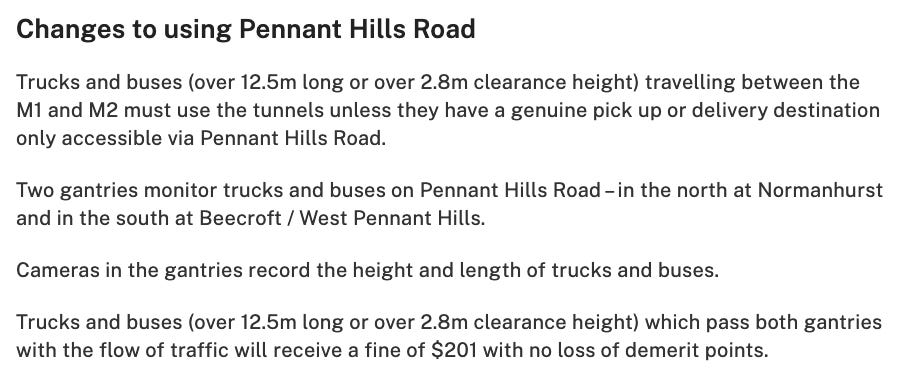

This is the type of charge Sydney has introduced for one vehicle type in one corridor. In northern Sydney, if a large truck is detected moving through the corridor on the surface road rather than on the tollway, they incur a penalty. This charge on through traffic generates higher asset revenue through tolls (and penalties), fewer truck trips on surface roads and travel time savings for the trucking operators.

Seattle could also throw a cordon around the surface streets in the tunnel corridor and apply a ‘tunnel charge’ to all through traffic on the tunnel axis. People using surface roads would pay a fee if, for example, they entered the corridor cordon from the north and exited to the south within 30 minutes. If they entered the corridor cordon from the north, stayed two hours and exited to the south, or if they entered the cordon in the north and left to the north, there would be no corridor-based asset charge.

This charge would encourage those wriggling through the centre of Seattle on surface roads to shift their through trip to the tunnel.

Of course, it is not just Seattle that would benefit from a zone-based charge that pushed through traffic onto existing bypass routes. In the central areas of Sydney and Melbourne, through trips by car are a significant proportion of the road traffic but contribute nothing to the centre and impose a significant cost on everyone else. Imagine what the central areas of those cities would be like with around 40% less traffic!

A first step

You could think of a cordon that imposes a charge on through traffic as the first step towards the use of the cordon to impose a charge to enter the central area – a destination charge.

If the proportion of through traffic is small, the effect of a through-traffic charge will be small - the through traffic reduction caused by the Stockholm charge was ~1% of the load. But in centres like Melbourne and Sydney with high levels of through traffic, the effect could be substantial and might on its own reduce the load enough to restore free flow speeds.

Even if a through-traffic charge proved to be a magic wand that reduced through traffic in the centre and restored free flow speeds, it is likely that over time, the load would grow and speeds fall, as the destination trips increased to fill the vacated road space. Come that time, a city with a working cordon that gathered real time load data and was able to detect and take payments from drivers, would be well placed to make the case for and then implement a charge on all vehicles.

New York

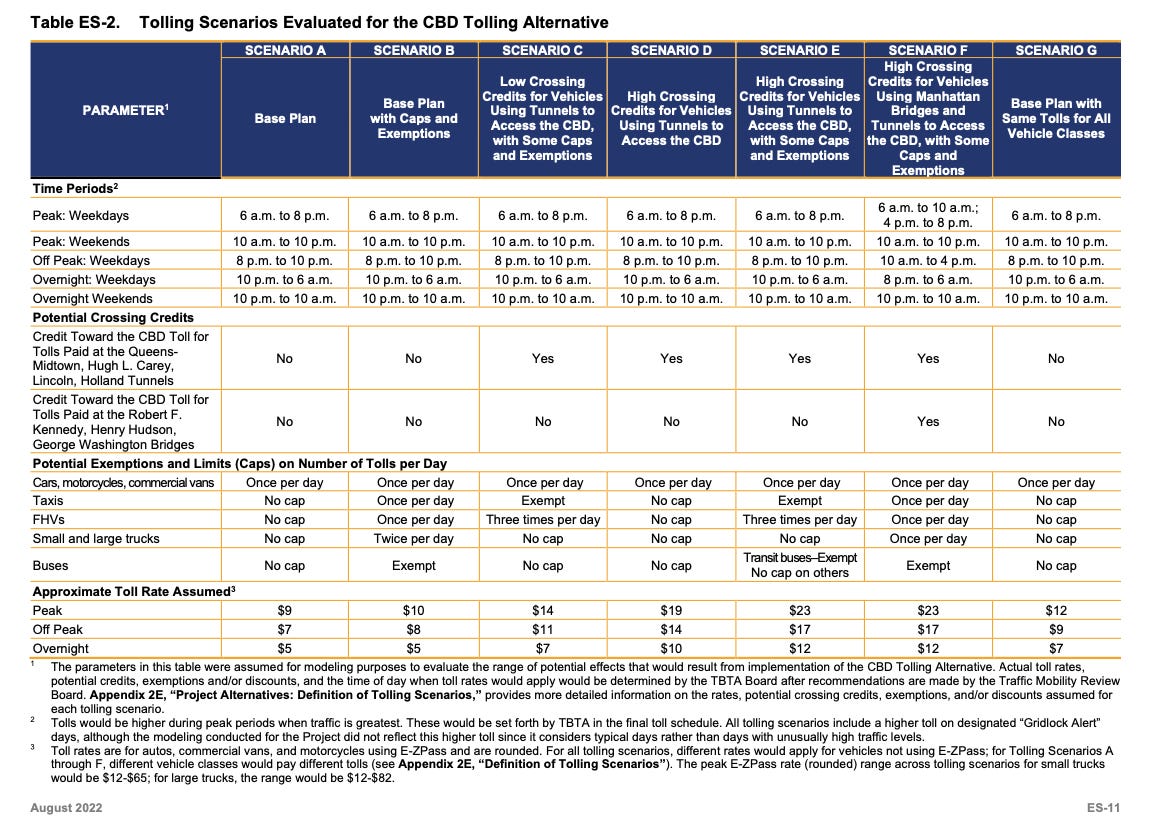

Of course, you can start from day one with a zone-based charge on all traffic. This is what New York plans with a road price cordon around the southern end of Manhattan Island. The final system settings have not been confirmed – nor has the charge been approved – but we can see the broad architecture in the detailed proposal documents.

The Manhattan story belongs here in our survey along with Seattle and Louisville because it is also (in part) an asset fee intended to raise revenue to pay off a whopping loan. Unlike the latter systems, the surplus revenue in Manhattan will be directed to the subway and other transit. (Later we will meet other systems that use surplus revenue in this way including the system in Perth where parking fees fund public transport services.)

The marketing and public expectation department is promoting the Manhattan scheme as a congestion charge, so the scheme has that intention as well.

The zone

Let us start with the design of the zone which establishes an unavoidable cordon stretching across all access routes: bridges, tunnels, and the north-south surface roads on the island itself.

The zone takes advantage of physical geography, using the Hudson River as a boundary on three sides. Stockholm also relies on water to establish its zone boundaries. Less watery centres such as London, Melbourne and Sydney do not have this advantage and must develop more arbitrary dividing lines on land. Manhattan establishes its land boundary, not on the water at the northern end of the island, but by anchoring it to Central Park.

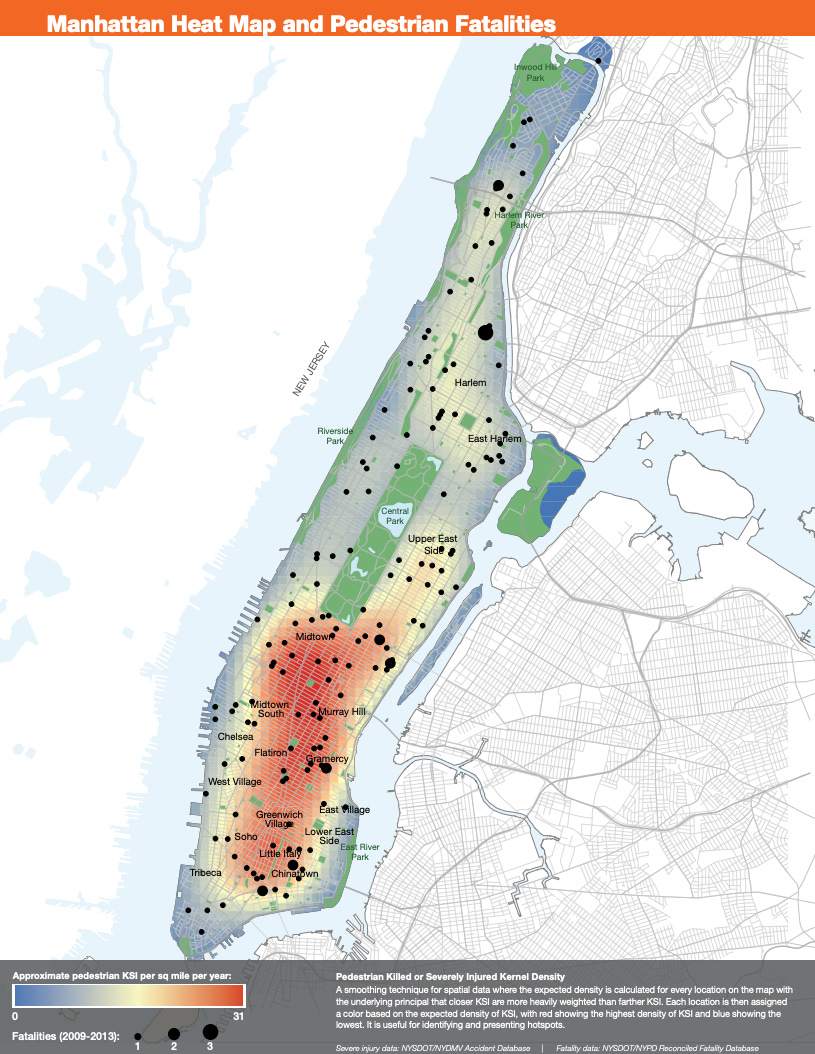

The zone fits neatly over the high density, high activity central area with its strong magnetic attraction – people want to go to Manhattan (not just for employment) and the alternative destinations are not as compelling. The pedestrian activity and fatality heat map below illustrates the intensity of activity inside the zone. Most of the people who come to the zone come by active and public transport and the motor vehicle is a minor mode (24%) a pattern found in many central city areas including in Australia.

This favourable physical and urban geography put Manhattan in a strong position. However, the current road pricing landscape is less favourable. Today, some who drive are used to paying a toll while others cross bridges as free riders. This means several pricing questions must be answered. One is what should the opening fee be for those who currently luxuriate in a toll-free crossing? Another is should today’s toll payers cough up an additional fee?

The proposed fees are yet to be decided and range in the proposal from $9US to $23US. (~$13 to ~ $35). (While in Manhattan we will stick to US dollars.) For those already paying a toll, the fees may vary between an amount in that range and nothing.

The load & the tariff

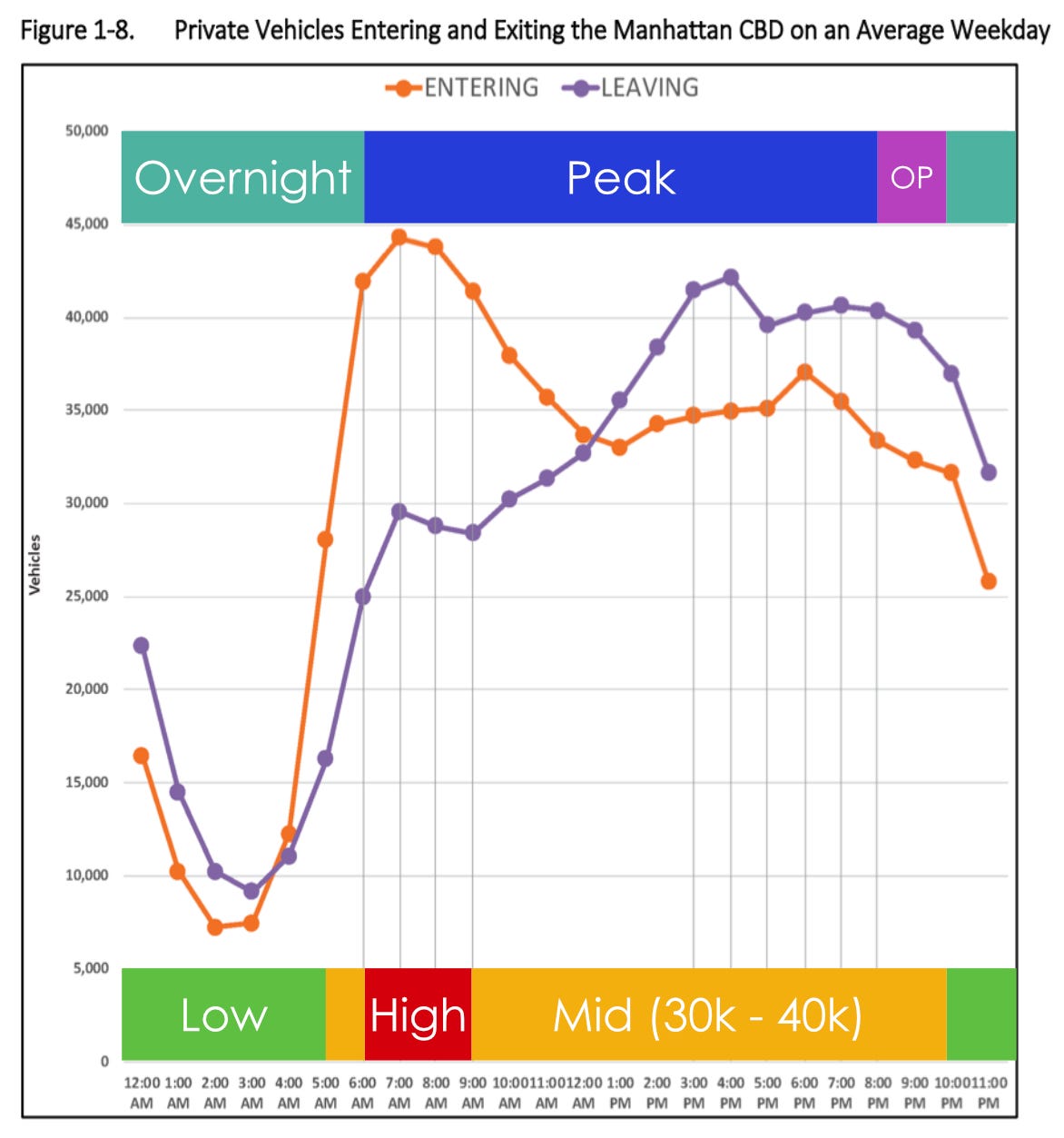

From the proposal documents we know the observed load and the proposed opening fees. (The unmodified load chart and draft tariffs are below.)

The dotted orange line on the chart shows the inbound load fluctuating between a high of 45,000 vehicles per hour and an overnight low of 7,000. For much of the day the in-bound load is in the 30s.

The modified chart shows red, amber, and green label blocks along the bottom. These divide the load into high, medium, and low bands based on a mid-load of 30 - 40,000 vehicles. The broad time bands for the load appear to be a low load from midnight – 05:00, a mid-load hour, then a high load period 06:00 – 09:00 followed by a mid-load period 09:00 – 20:00, before a period of low load to midnight.

The proposed weekday tariff is represented by the label blocks added to the top of the modified load chart. The peak charge is proposed between 06:00 – 20:00. An off-peak charge operates 20:00 – 22:00, followed by an overnight charge 22:00 – 06:00.

It is interesting that the proposed tariff does not reflect the load. For example, the proposed tariff does not impose a higher charge on the peak of the peak between 06:00 – 09:00 when the load is in the 40s. The charge drops to an off-peak rate while the load is still in the 30s. The charge does not switch off when the load is in the teens.

The aim

Using this zone and this tariff, the Manhattan scheme aims to raise revenue and reduce the number of inbound trips. The revenue target is $15b to improve subway, bus, and commuter rail systems, while the Pigouvian target is to reduce inbound vehicles by 10% and vehicle kilometres travelled by 5%. (London aimed for a 10 – 15% reduction of vehicles in the centre and a speed increase of 20-30%.)

The Manhattan scheme is careful to always mention both goals as if they were two sides of the same coin. The formal goal statement is to ‘reduce traffic congestion in the Manhattan CBD in a manner that will generate revenue for future transportation improvements’. Speaking to a reporter for the Gothamist, a senior transport official said ‘This is different than a typical tolling system. [In a] typical tolling system you’re tolling for upkeep of the facilities. In this case we’re really tolling to help reduce congestion and then raise the revenue for transit, which further reduces congestion.’

In other words, they imagine a virtuous circle in which virtuous chickens will lay virtuous eggs.

Possible outcomes

The Manhattan charge may indeed achieve both aims but there are other possible outcomes. It may generate revenue without suppressing the load (like London) and it may cut the load and miss the revenue target (like Seattle).

If they could only get one of those outcomes, which would they choose?

We will talk about that next time as we explore this ambitious scheme.

If they can make it there…